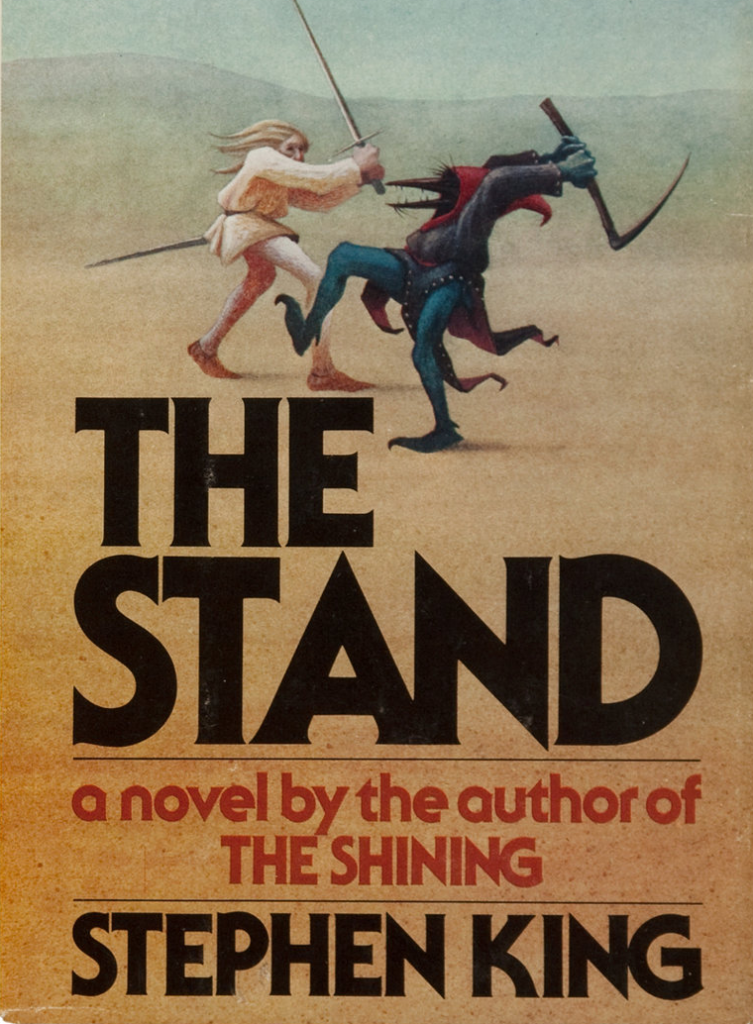

I read The Stand soon after it came out, so the version I know is a bit shorter than later versions. I read The Stand in high school, over three nights in the wee hours when I was supposed to be sleeping. Each night, I intended to read just a little bit more, then suddenly, it seemed, the flashlight was running out of battery power and it was 5 a.m., time for a couple of hours of catnap before school. This book convinced me that Stephen King is the King of Characterization, and pretty much everything else I’ve read by King confirms that. The Stand begins with a bang, then settles down and follows many individual characters and sets of characters. Action–wise, very little happens for the next 400 pages except the journeys of the individuals and groups as they begin to coalesce into two camps. That 400 pages could have been tedious; instead, it was riveting. King showed everything about these characters so you got to know them, their foibles, their hearts. Good tinged by evil, evil tinged by good. By the time action started up again, you not only knew the characters, you cared about many of them deeply.

I read The Stand soon after it came out, so the version I know is a bit shorter than later versions. I read The Stand in high school, over three nights in the wee hours when I was supposed to be sleeping. Each night, I intended to read just a little bit more, then suddenly, it seemed, the flashlight was running out of battery power and it was 5 a.m., time for a couple of hours of catnap before school.

This book convinced me that Stephen King is the King of Characterization, and pretty much everything else I’ve read by King confirms that. The Stand begins with a bang, then settles down and follows many individual characters and sets of characters. Action–wise, very little happens for the next 400 pages except the journeys of the individuals and groups as they begin to coalesce into two camps. That 400 pages could have been tedious; instead, it was riveting. King showed everything about these characters so you got to know them, their foibles, their hearts. Good tinged by evil, evil tinged by good. By the time action started up again, you not only knew the characters, you cared about many of them deeply.

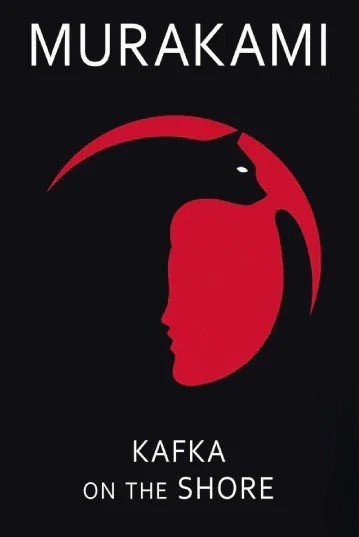

This is first Murakami book I read, loaned by a friend who thought I’d like Murakami’s work. He was right. I’ve now read a lot of Murakami’s work and look forward to every new book. Kafka was my introduction to Murakami’s brand of magical realism. His seamless blend of and transitions between reality and surreality create a very unusual atmosphere where everything is possible and everything is interesting (as opposed to the old writing trope “when everything is possible, nothing is interesting”; it is, as Eric Clapton wrote, in the way that you use it). Kafka could be considered as a coming–of–age story, as a mystical journey, or as a look beneath the thin and fraying throw–rug of reality. Or as all three and more. Kafka introduces you to people at tipping points in their lives, Colonel Sanders (yes, that Colonel Sanders of fried chicken fame), Johnny Walker (yes, that Johnny Walker of whiskey fame), and a very interesting and usual cat, among others. This book is a great intro to Murakami, but I have a warning: you might find his stories to be addictive. I did.

This is first Murakami book I read, loaned by a friend who thought I’d like Murakami’s work. He was right. I’ve now read a lot of Murakami’s work and look forward to every new book. Kafka was my introduction to Murakami’s brand of magical realism. His seamless blend of and transitions between reality and surreality create a very unusual atmosphere where everything is possible and everything is interesting (as opposed to the old writing trope “when everything is possible, nothing is interesting”; it is, as Eric Clapton wrote, in the way that you use it).

Kafka could be considered as a coming–of–age story, as a mystical journey, or as a look beneath the thin and fraying throw–rug of reality. Or as all three and more. Kafka introduces you to people at tipping points in their lives, Colonel Sanders (yes, that Colonel Sanders of fried chicken fame), Johnny Walker (yes, that Johnny Walker of whiskey fame), and a very interesting and usual cat, among others. This book is a great intro to Murakami, but I have a warning: you might find his stories to be addictive. I did.

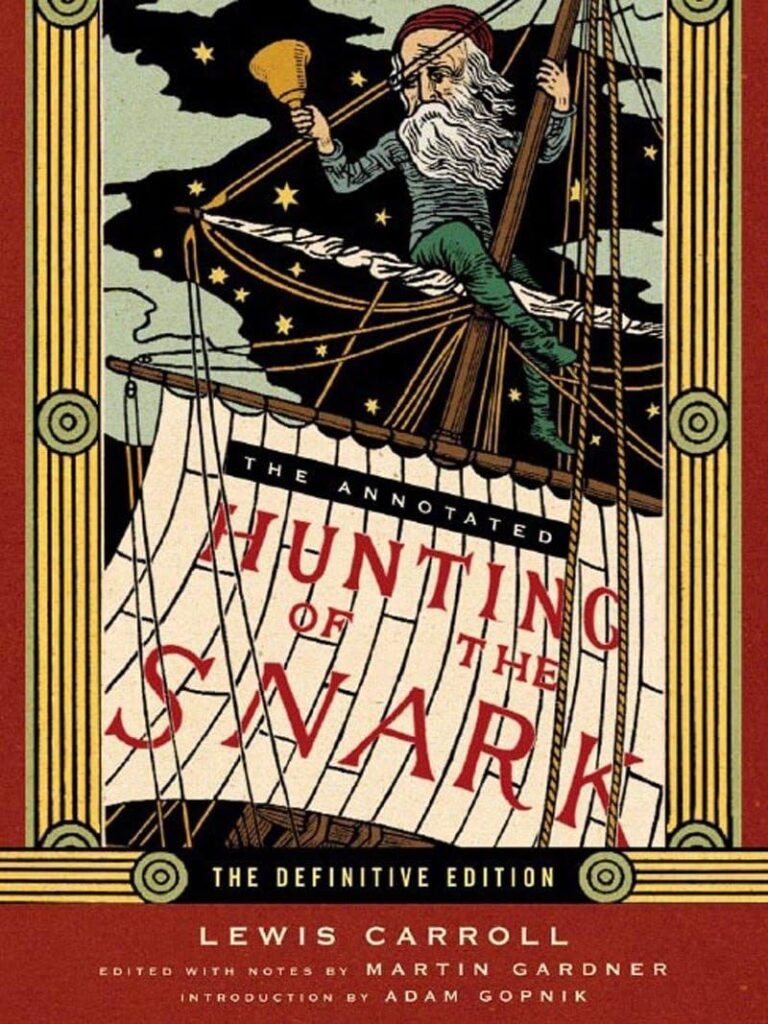

This poem in eight “Fits” is one of my two favorite Carroll poems, and my favorite “standalone” poem (poem not embedded in another story). I have fond memories of reading it to my daughter, employing different voices for each of the characters. It’s a wonderfully entertaining tale set in verse, about a motley collection of characters hunting for the mystical creature known as the Snark—but you definitely have to watch out for Boojums on your hunt. My other favorite Carroll poem is You Are Old, Father William, a laugh–out–loud romp from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (it’s in Chapter 5; Alice recites it to the Caterpillar). Other great poems to look for are the more famous The Walrus and the Carpenter and Jabberwocky (both from Through the Looking Glass), and the less famous but hilarious Peter and Paul (from Sylvie and Bruno).

This poem in eight “Fits” is one of my two favorite Carroll poems, and my favorite “standalone” poem (poem not embedded in another story). I have fond memories of reading it to my daughter, employing different voices for each of the characters. It’s a wonderfully entertaining tale set in verse, about a motley collection of characters hunting for the mystical creature known as the Snark—but you definitely have to watch out for Boojums on your hunt.

My other favorite Carroll poem is You Are Old, Father William, a laugh–out–loud romp from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (it’s in Chapter 5; Alice recites it to the Caterpillar). Other great poems to look for are the more famous The Walrus and the Carpenter and Jabberwocky (both from Through the Looking Glass), and the less famous but hilarious Peter and Paul (from Sylvie and Bruno).

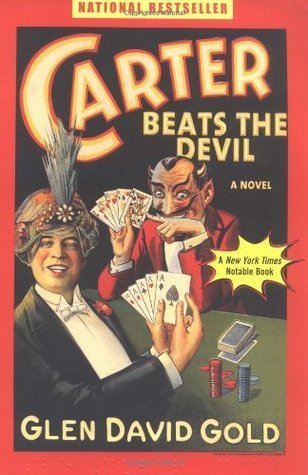

I’ve never read, or reread, another story like this. It’s hard to know how much is true history and how much is historical fiction. Gold masterfully blends real–life people like President Warren G. Harding, television pioneer and inventor Philo Farnsworth, and even the protagonist, magician Charles Joseph Carter, with a supporting cast of fictional characters to create a fictionalized world around Carter’s real career and Harding’s real death in San Francisco in 1923. The prose is easy to read. My father, who was born in Oakland, recognized the places Gold wrote about when he read the book. This book is simply a great story and a great read.

I’ve never read, or reread, another story like this. It’s hard to know how much is true history and how much is historical fiction. Gold masterfully blends real–life people like President Warren G. Harding, television pioneer and inventor Philo Farnsworth, and even the protagonist, magician Charles Joseph Carter, with a supporting cast of fictional characters to create a fictionalized world around Carter’s real career and Harding’s real death in San Francisco in 1923.

The prose is easy to read. My father, who was born in Oakland, recognized the places Gold wrote about when he read the book. This book is simply a great story and a great read.

For me, this is not just Card’s best book and a great science fiction book, it’s one of the best books I’ve read in any genre. The idea of using children for warfare isn’t new, although it probably isn’t overused, either. The idea of conflict with aliens isn’t new, although it may well be overused. The way Card fuses these ideas, mixes them with gaming before immersive games were around, mixes them with deep moral questions about humanity, and the depth and personal lives and conflicts of the characters, set this book apart. (No matter how interesting the plot, it almost always comes back to character in the end.)

For me, this is not just Card’s best book and a great science fiction book, it’s one of the best books I’ve read in any genre. The idea of using children for warfare isn’t new, although it probably isn’t overused, either. The idea of conflict with aliens isn’t new, although it may well be overused. The way Card fuses these ideas, mixes them with gaming before immersive games were around, mixes them with deep moral questions about humanity,

and the depth and personal lives and conflicts of the characters, set this book apart. (No matter how interesting the plot, it almost always comes back to character in the end.)

This is the first book I read by McCarthy and it was part of my drive to read authors that I “should” read but haven’t read. To say The Road is dark is sort of like saying that looking directly into the sun is bright. But on the road, despite no reason at all for optimism and every reason to give up, the father’s struggles to preserve his son and give him some sort of hope when all around seems lost, are enough to carry the reader through the impaling darkness. I won’t give away the ending but will say that maybe, maybe, in all that darkness, there is, like a stream of bat’s piss in the night, a shaft of golden light (thank you Monty Python for that image). But it could just be bat’s piss.

This is the first book I read by McCarthy and it was part of my drive to read authors that I “should” read but haven’t read. To say The Road is dark is sort of like saying that looking directly into the sun is bright. But on the road, despite no reason at all for optimism and every reason to give up, the father’s struggles to preserve his son and give him some sort of hope when all around seems lost, are enough to carry the reader through the impaling darkness.

I won’t give away the ending but will say that maybe, maybe, in all that darkness, there is, like a stream of bat’s piss in the night, a shaft of golden light (thank you Monty Python for that image). But it could just be bat’s piss.

This book chronicles the time–sliding adventures of a Pilgrim. Billy Pilgrim, who experiences and survives not only the bombing of Dresden in World War II, but gear–slips in time and space and travels to far off Tralfamadore. The story is strange and vulnerable and human and very anti–war, in the insightful, incisive style that marks Vonnegut’s writing. (Vonnegut survived the bombing of Dresden, where he was held as a prisoner of war along with other soldiers. In the book, his descriptions of Dresden and the bombing are from his personal experience.) If you read this book and feel nothing, I will doubt your humanity.

This book chronicles the time–sliding adventures of a Pilgrim. Billy Pilgrim, who experiences and survives not only the bombing of Dresden in World War II, but gear–slips in time and space and travels to far off Tralfamadore. The story is strange and vulnerable and human and very anti–war, in the insightful, incisive style that marks Vonnegut’s writing. (Vonnegut survived the bombing of Dresden, where he was held as a prisoner of war along with other soldiers.

In the book, his descriptions of Dresden and the bombing are from his personal experience.) If you read this book and feel nothing, I will doubt your humanity.

I was almost halfway through this book and as I read, I wondered what the point was. Gonzales told stories of survival against great odds—how people survived, the methods they used and their thought processes—but Gonzales never tied them together, never pointed out commonalities. I absorbed each story as a standalone, individual incident and tried to learn lessons from each.

Then a funny thing happened on the way to the end of the book. General patterns began to emerge. The general thought process and attitude of survival began to emerge. From what had appeared to be random methods and thought processes individual to each survivor and situation, there emerged something that I could take into real life. This was not in the form of exactly what to do in any given situation, but in how to approach survival situations, how to think about them, how to prepare for them mentally and emotionally, and how to react to them.

I was almost halfway through this book and as I read, I wondered what the point was. Gonzales told stories of survival against great odds—how people survived, the methods they used and their thought processes—but Gonzales never tied them together, never pointed out commonalities. I absorbed each story as a standalone, individual incident and tried to learn lessons from each.

To sum it up in one word: Awareness. That was really the common thread. But I wouldn’t be able to achieve that awareness if I had just been told the lessons in a “remember this” manner. That wouldn’t have had the necessary impact. Reading the stories in the book and letting the “back of your mind” go to work on them is the way to really grasp the lesson of how to be aware in situations where your survival and the survival of others is at stake.

If you like to spend time in nature, especially climbing, or hiking in remote regions, or doing anything that exposes you to that type of risk, I can’t recommend this book highly enough. Even if you don’t do those types of things, the awareness this book endows you with is applicable to potential risks in cities across the world.

Then a funny thing happened on the way to the end of the book. General patterns began to emerge. The general thought process and attitude of survival began to emerge. From what had appeared to be random methods and thought processes individual to each survivor and situation, there emerged something that I could take into real life. This was not in the form of exactly what to do in any given situation, but in how to approach survival situations, how to think about them, how to prepare for them mentally and emotionally, and how to react to them.

To sum it up in one word: Awareness. That was really the common thread. But I wouldn’t be able to achieve that awareness if I had just been told the lessons in a “remember this” manner. That wouldn’t have had the necessary impact. Reading the stories in the book and letting the “back of your mind” go to work on them is the way to really grasp the lesson of how to be aware in situations where your survival and the survival of others is at stake.

If you like to spend time in nature, especially climbing, or hiking in remote regions, or doing anything that exposes you to that type of risk, I can’t recommend this book highly enough. Even if you don’t do those types of things, the awareness this book endows you with is applicable to potential risks in cities across the world.

This is the best short story I’ve read. It’s a fictionalized account of Crane’s experience in an open boat on the sea after the ship he was on, the Commodore, was wrecked. The story takes place in that open boat, a tiny dinghy. It doesn’t get maudlin, it gets real. You can feel the exhaustion of the sailors as they fight for their lives, battle the sea, battle their weariness. This is a great introduction to Crane, who died at the young age of 28, yet left an amazing legacy that includes his most famous work (also excellent), The Red Badge of Courage. Read The Open Boat and you’ll want to read more of this brilliant writer whose early death may have taken him off the radar for too many readers.

This is the best short story I’ve read. It’s a fictionalized account of Crane’s experience in an open boat on the sea after the ship he was on, the Commodore, was wrecked. The story takes place in that open boat, a tiny dinghy. It doesn’t get maudlin, it gets real. You can feel the exhaustion of the sailors as they fight for their lives, battle the sea, battle their weariness. This is a great introduction to Crane, who died at the young age of 28, yet left an amazing legacy that includes his most famous work (also excellent), The Red Badge of Courage.

Read The Open Boat and you’ll want to read more of this brilliant writer whose early death may have taken him off the radar for too many readers.

I loved this story of first human contact with alien life. Compared to his earlier novel The Martian, Weir expands his writing range to encompass a complex relationship between human and non–human. As with The Martian, the premise and scientific extrapolations are believable and well–explained, and

everything happens in a believable way. Weir’s writing, already good, improved as well. One of the great things about this story was familiarizing the non–human in a way that was not at all human, yet completely relatable. What I mean by that is that Weir created a non–human character who I could identify with and understand without ever making the non–human seem like a human, think like a human, or behave like a human.

I loved this story of first human contact with alien life. Compared to his earlier novel The Martian, Weir expands his writing range to encompass a complex relationship between human and non–human. As with The Martian, the premise and scientific extrapolations are believable and well–explained, and

everything happens in a believable way. Weir’s writing, already good, improved as well.

One of the great things about this story was familiarizing the non–human in a way that was not at all human, yet completely relatable. What I mean by that is that Weir created a non–human character who I could identify with and understand without ever making the non–human seem like a human, think like a human, or behave like a human.

This is the best book ever written for chess players. In his prime, no player has ever been better, relative to his peers, than Fischer. Some grandmasters crushed it in the opening, some in the middle game, and some in the end game. A few could dominate in two of the three phases. The only one who dominated all three phases of the game was Fischer. Opening variations were named after him when he discovered/created them. His middle–game combinations were akin to the brightest, most spectacular fireworks, and he was considered the best end–game player since Jose Raul Capablanca. This seminal book presents Fischer’s 60 most memorable games, annotated by Fischer, so you get an illuminated window into his thought processes as well as his game analysis. These are some of the most beautiful and amazing chess games ever played. I don’t say this lightly or as a rank amateur. (OK, maybe rank, but not an amateur.) When I was young, I reached the rank of 26th best chess player under 21 years of age in the United States and was a USCF National Master of Chess. If you’re a chess player and you want to improve, read this book.

This is the best book ever written for chess players. In his prime, no player has ever been better, relative to his peers, than Fischer. Some grandmasters crushed it in the opening, some in the middle game, and some in the end game. A few could dominate in two of the three phases. The only one who dominated all three phases of the game was Fischer. Opening variations were named after him when he discovered/created them.

His middle–game combinations were akin to the brightest, most spectacular fireworks, and he was considered the best end–game player since Jose Raul Capablanca. This seminal book presents Fischer’s 60 most memorable games, annotated by Fischer, so you get an illuminated window into his thought processes as well as his game analysis. These are some of the most beautiful and amazing chess games ever played. I don’t say this lightly or as a rank amateur. (OK, maybe rank, but not an amateur.) When I was young, I reached the rank of 26th best chess player under 21 years of age in the United States and was a USCF National Master of Chess. If you’re a chess player and you want to improve, read this book.

I know of no other work that has half as many quotable lines or has been referenced so many times. If you don’t want to read the play or are intimidated by the language, I recommend Kenneth Branagh’s amazing screen version of the play. As far as I know, it’s the only filmed version that includes every line of the play. It also has some surprising, fine performances by people you might not expect to see in a Shakespeare play, like Billy Crystal (gravedigger) and Charlton Heston (leader of the troupe of players who put on the play within the play). To me, Hamlet is good required reading—or at least viewing— because there are so many references to lines from Hamlet everywhere, in movies, in books, in other plays, in nighttime cartoons, everywhere. It also shows that human conflict defies the aging of time and distance; the scene may have changed, but humanity has not.

I know of no other work that has half as many quotable lines or has been referenced so many times. If you don’t want to read the play or are intimidated by the language, I recommend Kenneth Branagh’s amazing screen version of the play. As far as I know, it’s the only filmed version that includes every line of the play. It also has some surprising, fine performances by people you might not expect to see in a Shakespeare play, like Billy Crystal (gravedigger) and Charlton Heston (leader of the troupe of players who put on the play within the play).

To me, Hamlet is good required reading—or at least viewing— because there are so many references to lines from Hamlet everywhere, in movies, in books, in other plays, in nighttime cartoons, everywhere. It also shows that human conflict defies the aging of time and distance; the scene may have changed, but humanity has not.

I’d like to say more about this book but I don’t want to spoil anything, so I’ll just say this: even though you might see the ending “twist” coming from miles away, the book is fascinating and full of great lines. I found myself adhering sticky notes to page after page to mark a line to come back to. Here are a couple of examples:

I’d like to say more about this book but I don’t want to spoil anything, so I’ll just say this: even though you might see the ending “twist” coming from miles away, the book is fascinating and full of great lines. I found myself adhering sticky notes to page after page to mark a line to come back to. Here are a couple of examples:

The books in this long series don’t need to be read in order except for the first two books (you can read them first or last or not at all or at any point in the series, but the second book is a sequel of the first book). These books are bursting with memorable characters, fun and funny tongue–in–cheek anachronisms and anachronistic analogs of people both real (like Shakespeare) and fictional (like Conan the Barbarian), grinning–a–lot humor, and vivid imagination. The plots are clever in best meaning of the word and the prose flows in a way that makes the books hard to put down. I could name some favorites, but the thing is, they are all really good, fun reads.

The books in this long series don’t need to be read in order except for the first two books (you can read them first or last or not at all or at any point in the series, but the second book is a sequel of the first book). These books are bursting with memorable characters, fun and funny tongue–in–cheek anachronisms and anachronistic analogs of people both real (like Shakespeare) and fictional (like Conan the Barbarian), grinning–a–lot humor, and vivid imagination.

The plots are clever in best meaning of the word and the prose flows in a way that makes the books hard to put down. I could name some favorites, but the thing is, they are all really good, fun reads.

info@sleitnerbooks.com

+62 832-6200-86263

Designed by : Thrill Edge Technologies

Copyright © 2025. All rights reserved